INTRODUCTION

This Bible text was taken from Matthew 10 verse 39, and relates to verse 36 which reads: "and a man will find his enemies under his own roof". That is where these two officers found their enemies: amongst their colleaugues and friends. The two Australians were members of the "Bushveldt Carbineers", a British military unit which operated in the Northern Transvaal in the Spelonken area during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. It is a story of dash and feats, but also of intrigue, brutal murders, undisciplininary behaviour, ruthless actions, court-martials, sentencing and execution concerning these two men and their brothers-in-arms. Their story made headlines, especially in Australia. It is a story of a ruthless and undisciplined British military unit, headed by by persons who were never worthy of military officer's rank, the story of the murder of unarmed Boer soldiers who surrendered under the white flag, of innocent Boer women and children who were summarily executed, and of the murder of an innocent and neutral German missionary of the Berlin Missionary Society. The "Bushveldt Carbineers"

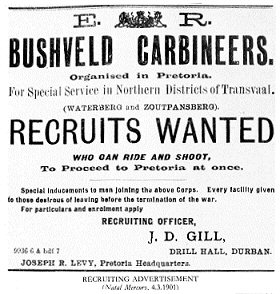

The Northern Transvaal, in the Soutpansberg ("salt lake mountains") area, was the last area of Boer resistance where small groups of Boer soldiers fought on relentlessly. Assistant commandant-general CF Beyers and Field Cornet WH Viljoen and their commandos caused the English forces headaches in this region. The Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) was established in April 1901 under the leadership of Maj R.W. Lenehan, an Australian, who soon proved himself incapable of commanding his subordinates. He suggested that Australians whose duty came to an end, be used, as well as "joiners" (Boers who deserted the Boer forces and joined the English cause). Members of the BVC were to receive double pay. There were never more than 350 members of the BVC, of which 70% were Australians, with the task to "purify" the area of the remaining Boer resistance. It was a rough band of unruly men consisting of mostly riff-raff and outcasts, many of whom were fortune-seekers who converged on the gold fields of South Africa, seeking a fortune, before the Anglo-Boer War, or Australian drifters who volunteered for service in the Anglo-Boer war. The Australian volunteers were mostly descendants of convicts, drawn from the Outback and the slums of large Australian cities, with little respect for law and order. It soon became apparent to members of the BVC that the Irishman capt Alfred Taylor, whose African nickname was "Bulala" ("killer"), was the real person in control of the BVC, dominating the weakling commanding officer Maj Lenehan. Taylor was a notorious sadist and murderer, which completely fitted Kitchener's desire to bring the war to an end as soon as possible, using whatever means possible. Henry Harbord Morant

Morant then started on a roaming career as a drifter. He became a master horse rider and earned a living breaking in horses, which gave him the nickname Breaker. He changed his name to Breaker Morant after his wife convinced him to do so. He worked on farms, spending his money in pubs and women, got involved in numerous fights, accumulating debts and then absconded, and in general conducting a reckless, wild and rumbustious life. He had many friends, was good company, helpful, and even tried his hand at poetry which was published in newspapers and magazines, mainly in the Sydney Bulletin. He was a womaniser and later became a heavy drinker. In October 1899 the Anglo-Boer War broke out in South Africa, something Morant welcomed as a new opportunity for adventure and employment. He could not wait joining the volunteer Australian mounted force, and left Adelaide on die SS Surrey on January 26th 1900 as corporal. Arriving in Cape Town, he was keen to demonstrate to the English soldiers how to handle horses, something they were ignorant about. He and his fellow Australians thought of themselves as having a superior knowledge of how to fight against the Boer forces in their natural environment. The British, until then, had still engaged in traditional European warfare. This behaviour of the "blasted Colonial horse stealers" offended the British, but Morant soon proved himself to be the expert horseman he was. He accompanied Roberts' troops for the siege of both Johannesburg and Pretoria. His tour of duty terminated nine months later on July 31st, 1900, and his unit returned to Australia without him, whilst he sailed for England, leaving behind some unpaid bills.. There he befriended Capt Percy Frederick Hunt, also back from duty in the Anglo-Boer War, and become engaged to Hunt's sister. When Kitchener called for reinforcements in December 1900, the two adventurers returned to South Africa for further service. Morant and Hunt both joined the BVC, and Morant was promoted to lieutenant on April 1st, 1901 and stationed at Fort Edward near Pietersburg in Northern Transvaal. Whilst some of his fellow officers adored him, many troops feared and some even hated him. Later a corp. H Sharpe testified that he "would walk 100 miles barefoot to Pietersburg to serve in a firing squad to execute Morant and Handcock."

The killing of Hunt and Eland

There were only 15 Boers staying overnight in Eland's farm house when Hunt and his party attacked them. The armed blacks fled when the shooting began. During the skirmish both Hunt and Eland were killed, whilst the Viljoen brothers were both also killed. When the rest of the party tried to attack the farmhouse again the next morning, they found only two dead Boers inside - Jacob Viljoen and G Hartzenberg, having been left behind by the fleeing Boer soldiers. Outside the bodies of Hunt and Eland lay, both stripped and mutilated, as was the body of Viljoen. It was later determided that both Hunt's and Viljoen's bodies were mutilated by black witchdoctors who arrived soon after the fight ended to remove body parts for ritualistic black magic medicine, known as "muti". A black messenger informed Morant at Fort Edward of the outcome of the fight, and Morant, Witton, Picton and Handcock arrived in Devil's Kloof the next day with 70 men, intent on revenging the deaths of Hunt and Eland, and the mutilation of Hunt's body, which he believed was done by the Boer soldiers. The murder of Floris Visser

Morant put the wounded Visser on a cart and proceeded to Fort Edward. On the second evening, August 11th 1901, they camped near a river; after supper a "Court-martial" was assembled (something which could only be done by senior officers, none of which were present). The court-martial consisted of Morant, Picton, Handcock and Witton, and it was decided to shoot Visser. Visser was not informed about the nature of the "trial" or the charges against him, and was given no opportunity so speak or make a defence. When told about the verdict, Visser reminded Morant that he had promised to spare his life as he had truthfully answered all the questions regarding the death of Hunt. Morant said:"It is idle talk. We are going to shoot you." He was carried to the banks of the river and made to sit since he could not stand, and a volunteer firing squad consisting of Tpr A Petrie and Tpr J Gill did its work. When Visser fell down but still showed signs of life, Lt H Picton walked up to him and emptied his revolver on Visser's head, blowing his brains out. Morant, Picton, Handcock and Witton were present at the execution. One of the blacks loyal to the Boers, when commmanded by Capt Taylor to reveal the whereabouts of a wounded Boer, curtly replied "Aikona", which was a direct refusal meaning "no way". Capt Taylor shot him dead with his revolver. Maj Lenehan and Col. Hall were informed of these murderous acts, but it was ignored and Morant was in fact congratulated on his actions against the Boer commandos, and was regarded as being in charge of Fort Edward. When Maj Lenehan was sent out to hold an inquiry, he endeavoured to bounce the troopers into giving evidence which would exonerate the officers. Particularly he tried to make them swear that the wounded Boer prisoner Visser was wearing the tunic of the late Capt Hunt, whereupon the witnesses (Corp T Gibbons, Sgt S Robinson, and Sgt-Maj T Clarke) pointed out that the clothes of the late Capt Hunt had continuously been worn by Morant who was wearing them himself at that moment. Morant wore the late Hunt's British Warm, riding breeches, tunic and leggings. When the witnesses refused to swear what Leneham required but swore that the prisoner was wearing only an old British shirt Leneham ordered the men out of his tent as if they had been dogs saying "That kind of evidence is no good tus us." The "Eight Boers" incident

Murder of the German missionary Heese

Heese proceeded and then an incident occurred between Fort Edward and Bandolierskop of which various versions exist. The fact is that both Heese and the black boy travelling with him were found dead, both shot. Silas, a black Christian, testified that Heese passed him; soon after a British officer followed on horseback. He heard shots, and on investigating, found the body of the dead black boy and the officer standing behind Heese's mule cart, still flying the white flag. Silas fled in fear, and informed the missionary O Krause of what he saw, who in turn reported the story to the officer in charge of the British forces in Pietersburg. The missionaries in the area requested the military authorities to investigate; a message was sent to Fort Edward, but a search party was sent out only six days later. Heese's body was found 60 yards from the road, shot through the chest, and was buried on the spot. On October 30th the corpse was dug up and reburied on Elim, next to the grave of Craig (who died after the operation). On August 23, 1904 Heese's body was again reburied on his missionary station Makapaanspoort, near Potgietersrus. Gensichen testified that the missionary was followed by a British officer, believed to be Handcock, "to eliminate a witness to the shooting of the Boer prisoners-of-war." Capt Frederick Ramon de Bertodano, of Spanish origin, was born in Australia and after a stay in England and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), was appinted as Information Officer on Kitchener's staff. He was posted in Pretoria and was responsible for information in the Northern Transvaal area. In 1928 he wrote down the "true story" of the BVC, which was later discovered in the National Archives in Salirsbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe). Being suspicious, he sent a telegram to Fort Edward, inquiring about Heese's death. On August 29th he received a telegram claiming that "Heese was shot by the Boers near Bandolierskop." De Bertodano subsequently sent two black scouts to Ford Edward to ascertain the truth. On the ninth day they returned, and one of them, Hans, reported what he learned from other blacks living in the area, namely that Handcock shot the black boy and Morant shot the missionary Heese. Morant had a black assistant who saw everything and told Hans the truth. This black assistant of Morant later mysteriously "disappeared", and there were no eyewitnesses to testify at the Court-martial which followed later. The "children"-incident

Another such incident occurred on September 7th when news reached the Fort that three Boers were on their way to surrender. Morant, Handcock, Witton and Botha left to meet them. Near Capt Taylor's house on Sweetwaters all three were taken into custody, disarmed and summarily shot dead, despite the fact that they carried a white flag. This murder almost led to mutiny amongst the soldiers stationed at Fort Edward. A group of 15 men and and NCO's send a protest letter on October 4th, 1901 to Lieut-Col FH Hall in Pietersburg, but Hall simply ignored it. Finally it was left to De Bertodano to bring things to closure when he started to investigate the behaviour of Morant and Handcock, after thoroughly investigating Taylor's activities. John Kelly caught

Court of Investigation

The Court-martials

It is a fact that no researcher

has been able to date to obtain a complete report of either the Court of

Investigation or the Court Martials from the War Office in England. The

seven volume "History of the War in South Africa" of The Times has

scant reference to the BVC and none to the Court-martials. Cutlack (FM

Cutlack: Breaker Morant: A Horseman Who Made History, Sydney, 1962)

writes: "I have requested from the War Office permission to peruse the

court-martial proceedings in the Morant case - now sixty years old - and

have been officially informed that these documents 'are no longer in existence'.

Margaret Carnegie (Margaret Carnegie & Frank Shields: In Search

of Breaker Morant, Armadale (Austr.), 1979) was informed in 1979 that

the court-martial records were During cross-examination Morant said that Hunt's orders were to clear Spelonken and take no prisoners. He had never seen these orders in writing, but took Hunt's word for it that Col Hamilton had given such orders. Picton stated that he opposed the shooting of Visser at the Court-martial, but nevertheless was put in command of the firing party, and merely obeyed orders. Morant was found guilty of the murder of Visser, and his colleagues Handcock, Witton and Picton guilty of manslaughter. For the murder of the eight Boers Morant, Handcock and Witton were found guilty. Morant's defence was that he simply carried out orders of senior officers "not to bring in any prisoners," and admitted to killing the Boer prisoners-of-war. Tpr Thompson testified that he, Tpr Duckett and Tpr Lucas were sent for by Morant, who asked about the shooting of the eight Boer prisoners. Lucas had objected to them being shot, but Morant said "I have orders and must obey them, and you are making a mistake if you think you are going to run the show." On the morning of the 23rd Thompson saw a party with eight Boers. Morant gave orders, and the prisoners were taken off the road and shot, Handcock killing two with his revolver. Morant afterwards told Thompson that they had to play into his hands, or else they would know what to expect. For the murder of the missionary Heese a second Court-martial was assembled with Lt-col F Macbean as president, and six members. The accused were Morant and Handcock. Handcock was accused of murder on instructions and incitement of Morant. Circumstantial evidence was delivered by various people, including H van Rooyen, but no witnesses could be produced. Handcock's alibi was that on the day of the murder he visited Mrs Schiel on her farm till after lunch, and was with Mrs Bristow until sunset. Both ladies confirmed this before the Court-martial. Due to a lack of evidence, both Handcock and Morant were found not guilty, although it was rumoured that most members of the Court-martial believed that they were indeed guilty, but that confirming evidence could not be found. After their acquittal two members of the Court-martial send six bottles of champagne to the accused, and they were allowed to spree throughout the night. Morant and Handcock were furthermore accused that they instructed certain troopers and a corporal to kill the three Boer prisoners-of-war on September 7th, 1900, and found guilty. During the Court-martial the court moved to Pretoria on January 24th to hear evidence from Col Hamilton, Kitchener's military secretary. The court asked him only two questions: did he ever issue orders "not to bring in any prisoners," and whether he ever talked to Capt Hunt. His answer to both questions were a curt "No!" It was told that he appeared to be extremely excited and nervous during the questioning. On January 31st the court again returned to Pietersburg. At one stage Handcock acknowledged, under great stress (as he stated: "...just to satisfy Col. ----"), that he was guilty of the murder of Heese and other murders. In the court he withdrew this statement. The written acknowledgement was never submitted to the court, and could not be found later. Wrench and the joiner Botha became crown witnesses. Handcock stood accused of the shooting of Tpr Van Buren, a member of the BVC and a local inhabitant, who was not trusted by himself and Morant. On witnessing the shootings of the eight Boer prisoners, Van Buren told their families who were also locals. Handcock took Tpr Van Buuren out on patrol from which only Handcock returned. Handcock stated that Van Buuren was shot by Boers. All accused were brought to trial from the evidence taken from 15 NCO's and soldiers from the BVC who were sickened by the actions which they were forced to partake. With evidence from other soldiers, Morant's and Handcock's fates were sealed. All seven officers were charged with real crimes (despite the innuendoes of the movie 'Breaker Morant'). The facts in all the proceedings were that all seven were guilty of the shootings either by direct action or by complicity. On the morning of February 21st, 1902 all accused were awakended early. Morant, Handcock, Witton and Picton were handcuffed, and taken by train to Pretoria. On February 26th they were informed of their sentences: Morant and Handcock were to be shot the next morning. Witton was sentenced to death but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Lt H Picton, the Englishman, was cashiered and therefore simply dismissed and his uniform, rank and decorations taken away. Lenehan was himself charged over instances of the shooting of Boer prisoners, but was only found guilty of failing to report such occurrences; he was reprimanded, relieved of his command and returned to Australia. Maj Thomas was dismayed and devastated when he heard of the sentences. He rushed to military headquarters to plea for commutation or postponement, but Kitchener made certain that he was out of town from the moment when the sentences were delivered. All efforts for reprieve were fruitless.

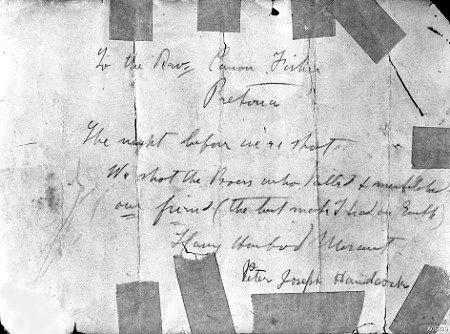

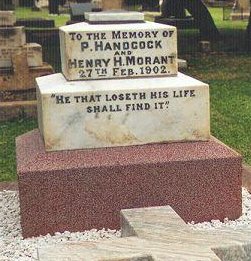

At six o'clock the morning of February 27th, 1902 Morant and Handcock were executed by eighteen men of the Cameron Higlanders under command of Lt Thompson. Morant smoked a last cigarette, refused to be blindfolded, and his final words were: "Shoot straight, you bastards, don't make a mess of it!" Australian fellow soldiers took their corpses and made certain that both were given a proper burial in the same grave in the Pretoria cemetery. In June 1998 the Australian Government spent $1,500 refurbishing the grave site with a new concrete slab and a new marble cross. The Australian government only heard about the Court-martials, verdicts and execution of its soldiers much later. Upset, they demanded an explanation from Kitchener who, on April 5th 1902, sent a telegram to the Australian Governor-General, and which was published completely in the Australian press. It reads as follows: "In reply to your telegram, Morant, Handcock and Witton were charged with twenty separate murders, including one of a German missionary who had witnessed other murders. Twelve of these murders were proved. From the evidence it appears that Morant was the originator of these crimes which Handcock carried out in cold-blooded manner. The murders were committed in the wildest parts of the Transvaal, known as Spelonken, about eighty miles north of Pretoria, on four separate dates namely 2nd July, 11th August, and 7th September. In one case, where eight Boer prisoners were murdered, it was alleged to have been done in a spirit of revenge for the ill treatment of one of their officents - lieutenant Hunt - who was killed in action. No such ill-treatment was proved. The prisoners were convicted after a most exhaustive trial, and were defended by counsel. There were, in my opinion, no extenuating circumstances. Lieutenant Witton was also convicted but I commuted the sentence to penal servitude for life, in consideration of his having been under the influence of Morant and Handcock. The proceedings have been sent home."This telegram caused an uproar in Australia, where it was generally believed that Kitchener suppressed the Court-martials. When Kitchener visited Australia in 1910, he was invited to unveil a memorial in Bathurst, New South Wales (Hancock's home state), on which the names of volunteers from the state who fought in the Anglo-Boer War appears. At the insistence of Kitchener, Hancock's name was removed from the list, but it was added on March 1st, 1964. A few days after the execution of Morant and Handcock the Boer joiner Theuns Botha was killed by an unknown person whilst he was riding on his white horse near the jail in Pretoria. It was generally believed that it was done by a Boer who regarded his as a despicable traitor. Witton was taken to England, arriving on April 2nd, 1902, and was incarcerated in jails in Gosport, Lewes and Portland. A petition to the king, signed by 100 000 Australians, for his release was ignored by the War Office. His life sentence was overturned by the British House of Commons and in July 1904 he was released, mainly as a result of the intervention of JD Logan, the "Laird of Matjiesfontein," in Cape Town. Witton left Liverpool on September 29th 1904, arriving back home on November 12th, 1904. In 1907 he published his version of the saga in his book "Scapegoats of the Empire," which was widely discredited. It is rumoured that the Australian government purchased the whole print, and less than ten copies survived. It was later reprinted. In conclusion

Witton saw both at supper on the evening of the murder. Morant convinced Handcock to withdraw his previous admission and the two decided to fabricate an alibi. This was successful, and resulted in them being not found guilty of the murder of Heese. They believed that Heese's murder was the only one on which they could be sentenced to death, and that they would be acquitted on the murders of Boer prisoners. Witton was of the opinion that if there had been no Heese incident, the execution of Boer prisoners would not have attracted any attention. He was, however, of the opinion that the murder on Heese was pre-planned and cold-blooded. "Handcock told me everything personally; but, because Morant and Handcock were found not guilty, my lips were sealed." Why were Wittons lips sealed for 27 years? Possibly in consideration of Handcock's family, who firmly believed in his innocence. This letter of Witton is filed in the Mitchell-library in Sydney and was, according to instructions, only released in 1970. Kitchener, in an attempt

to get the whole messy affair behind his back, widely published the information

regarding the charges and convictions in the"Army Orders" the day after

the execution. Later accusations that Kitchener tried to cover-up the affair

was thereby nullified.

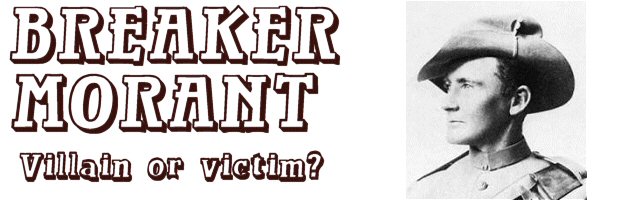

A fact that upset the Australians is that two Australians only were found guilty, and that they were convicted by a British Court-martial, whilst Taylor, Robertson and Morrison were found not guilty of the murder of six Boer prisoners. Many other cases of the shooting by English soldiers of Boer soldiers who surrendered with a white flag, were simply ignored. Furthermore, the fact that the sentences were kept secret until a day before the execution of Morant and Handcock, and that the transcripts of the proceedings went missing, upset many. Their case (and one other) were responsible for the Australian Government's decision never to place Australians under total foreign legal command ever again. In WW1, although over 150 Australians were sentenced to death by British courts-martial, not one was executed as the Australian Governor General always refused to sign the order. A romanticised movie of Morant's life and adventures, "Breaker Morant," in which he is depicted in a sympathetic way as someone against whom an injustice was done, was completed by Beresford and released in July 1980 in Australia. The movie is largely based upon nationalistic folklore, such as George Witton's book "Scapegoats of the Empire" (1907), the novel by Kit Denton called "The Breaker" (1973) and Beresford's own republican leanings. That the realities of Morant's life are different from the legend should not be surprising; that they differ as greatly as they do, should be. Beresford, in the desire to make a nationalistic film, grossly distorted historical facts and glossed over the real issues of wartime morality. The controversy about the

Morand and Handcock case continues. Their supporters regard them as martyrs

and victims of British imerialism. Outside of Australia they are regarded

as villains and murderers who received their just resard for what they

did

References and recommended reading:

|

After

the occupation of Pretoria on June 5th, 1900 the "commando tactics" of

the Boer generals Louis Botha, Christiaan de Wet, Koos de la Rey, Jan Smuts,

Ben Viljoen and Christiaan Beyers began. Most Boer commandos split up into

groups of 100 or smaller and kept the British forces at bay for another

18 months. Kitchener started his infamous strategy of concenctration camps

for Boer women and children (in which 27 000 of them died, about one fifth

of the total population) and the "scorched earth" policy of the burning

of Boer homesteads and harvests, and the killing of all their livestock.

After

the occupation of Pretoria on June 5th, 1900 the "commando tactics" of

the Boer generals Louis Botha, Christiaan de Wet, Koos de la Rey, Jan Smuts,

Ben Viljoen and Christiaan Beyers began. Most Boer commandos split up into

groups of 100 or smaller and kept the British forces at bay for another

18 months. Kitchener started his infamous strategy of concenctration camps

for Boer women and children (in which 27 000 of them died, about one fifth

of the total population) and the "scorched earth" policy of the burning

of Boer homesteads and harvests, and the killing of all their livestock.

Carl

August Daniel Heese was a missionary of the Berlin Mission's missionary

station Makapaanspoort near Potgietersrus. In August 1901 he took a Mr

Craig, which ran a small shop between Malokong and Makapaanspoort, to the

Swiss missionary hospital at Elim for an operation on a swollen thyroid

gland. Heese stayed for a couple of days to take Craig back after he had

recuperated, (but Craig later died of complications). On Friday morning

August 23rd Heese took his usual morning walk and came upon a wagon on

which eight Boer prisoners-of-war were sitting. He greeted them and talked

to WD Vahrmeyer, a teacher from Potgietersrus. He informed Heese that they

were worried because rumours had it that the British forces killed prisoners-of-war.

A guard wanted to arrest Heese, but he showed his travel permit. Heese

returned home during the afternoon, and passed the scene where the eight

Boer prisoners-of-war were shot, seeing their dead bodies, each with a

bullet hole in the forehead. When Heese and a black boy accompanying him

passed Fort Edward in his mule cart, Morant warned him that he may be troubled

by Boer forces operating in the area. When he insisted to travel ahead,

he was advised to put a white flag on his mule cart.

Carl

August Daniel Heese was a missionary of the Berlin Mission's missionary

station Makapaanspoort near Potgietersrus. In August 1901 he took a Mr

Craig, which ran a small shop between Malokong and Makapaanspoort, to the

Swiss missionary hospital at Elim for an operation on a swollen thyroid

gland. Heese stayed for a couple of days to take Craig back after he had

recuperated, (but Craig later died of complications). On Friday morning

August 23rd Heese took his usual morning walk and came upon a wagon on

which eight Boer prisoners-of-war were sitting. He greeted them and talked

to WD Vahrmeyer, a teacher from Potgietersrus. He informed Heese that they

were worried because rumours had it that the British forces killed prisoners-of-war.

A guard wanted to arrest Heese, but he showed his travel permit. Heese

returned home during the afternoon, and passed the scene where the eight

Boer prisoners-of-war were shot, seeing their dead bodies, each with a

bullet hole in the forehead. When Heese and a black boy accompanying him

passed Fort Edward in his mule cart, Morant warned him that he may be troubled

by Boer forces operating in the area. When he insisted to travel ahead,

he was advised to put a white flag on his mule cart.

destroyed.

Witton's subjective and generally unreliable book (GR Witton: Scapegoats

of the Empire: The Story of the Bushveldt Carbineers, Melbourne, 1907)

publishes the only (albeit incomplete) verbatim record of the evidence

as well as the findings of the court-martials, but is selective with notable

omissions of damning evidence against the accused. (De Bertodano caustically

declared that Witton's book was "mostly a garbled and untrue version

of the facts.... When the book was published, it was largely bought up

by the Govt. as a false presentation of what occurred.".) Evidence

of Witton's unreliability is his initial insistince in the book that he

was "astounded" to hear that the death of missionary Heese had been laid

at the door of Lt Handcock and that he had "not the slightest reason"

to connect him with it. Writing to Maj JF Thomas, long afterwards on 29

October 1929, Witton made a statement that raises eyebrows about his general

credibility for he stated that Handcock had told him all about the shooting

of Heese. It had been, said Witton in this belated admission, "a premeditated

and most cold blooded affair," without divulging whether it was Handcock

or Morant himself who shot Heese. A large number of depositions are, however,

available, containing damning evidence against the accused. To date the

best source of the Court-martials and depositions is Arthur Davey's "Breaker

Morant and the Bushveldt Carbineers."

destroyed.

Witton's subjective and generally unreliable book (GR Witton: Scapegoats

of the Empire: The Story of the Bushveldt Carbineers, Melbourne, 1907)

publishes the only (albeit incomplete) verbatim record of the evidence

as well as the findings of the court-martials, but is selective with notable

omissions of damning evidence against the accused. (De Bertodano caustically

declared that Witton's book was "mostly a garbled and untrue version

of the facts.... When the book was published, it was largely bought up

by the Govt. as a false presentation of what occurred.".) Evidence

of Witton's unreliability is his initial insistince in the book that he

was "astounded" to hear that the death of missionary Heese had been laid

at the door of Lt Handcock and that he had "not the slightest reason"

to connect him with it. Writing to Maj JF Thomas, long afterwards on 29

October 1929, Witton made a statement that raises eyebrows about his general

credibility for he stated that Handcock had told him all about the shooting

of Heese. It had been, said Witton in this belated admission, "a premeditated

and most cold blooded affair," without divulging whether it was Handcock

or Morant himself who shot Heese. A large number of depositions are, however,

available, containing damning evidence against the accused. To date the

best source of the Court-martials and depositions is Arthur Davey's "Breaker

Morant and the Bushveldt Carbineers."